Arguably, the first person to die in the American Revolution was a Black man: Crispus Attucks, gunned down in Boston by British soldiers on March 5, 1770. The context of the murder was a colonial city outraged by British measures to raise revenue and maintain public order. After the passage of a series of taxes in 1767, a British naval squadron dropped anchor in Boston Harbor to enforce them (See Image). The Navy conscripted several people, and seized John Hancock’s sloop Liberty for non-payment of duties. Angry townspeople protested, a riot ensued, and a pleasure boat belonging to the collector of customs was brought ashore and burned in the Common.

"The Bloody Massacre" engraved by Paul Revere, 1770 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute)

Several clashes followed, including one in which an 11-year-old boy was killed. Then, around nine in the evening on March 5, 1770, an angry crowd confronted British soldiers stationed in front of the Customs House on King Street. One of the people in that crowd was Attucks – described as a “Molatto” -- whom one eyewitness later said had been “at the head of twenty or thirty sailors” marching up the hill from the wharf, and who carried “a large cordwood stick.” By one account, this man raised his arm against a British soldier, or perhaps had thrown something. Soldiers fired and two musket balls stilled Attucks’ heart. Four others were killed as well (See Image).

The Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770, William L. Champney, 1856 Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Boston Massacre proved to be one of a series of events, including the Boston Tea Party in ‘73, the convening of the First Continental Congress in ‘74, and the battles at Lexington and Concord in ‘75, which historians argue tipped the colonies into revolution. For African-American Bostonians Attucks was the first “martyr” to democracy. They constructed a memorial to him in 1888, transforming him into the founding first-citizen of a multi-racial nation (See Image).[1]

The Crispus Attucks Memorial, Boston

For other Americans, the nation may have begun at the moment immortalized in John Trumbull’s painting, which hangs in the Capitol Rotunda, and which depicts the day in 1776 (June 28), when the drafting committee, headed by Thomas Jefferson, presented the Declaration of Independence to the rest of the Congress (See Image).[2]

Declaration of Independence, John Trumbull, 1817, U.S. Capitol Rotunda

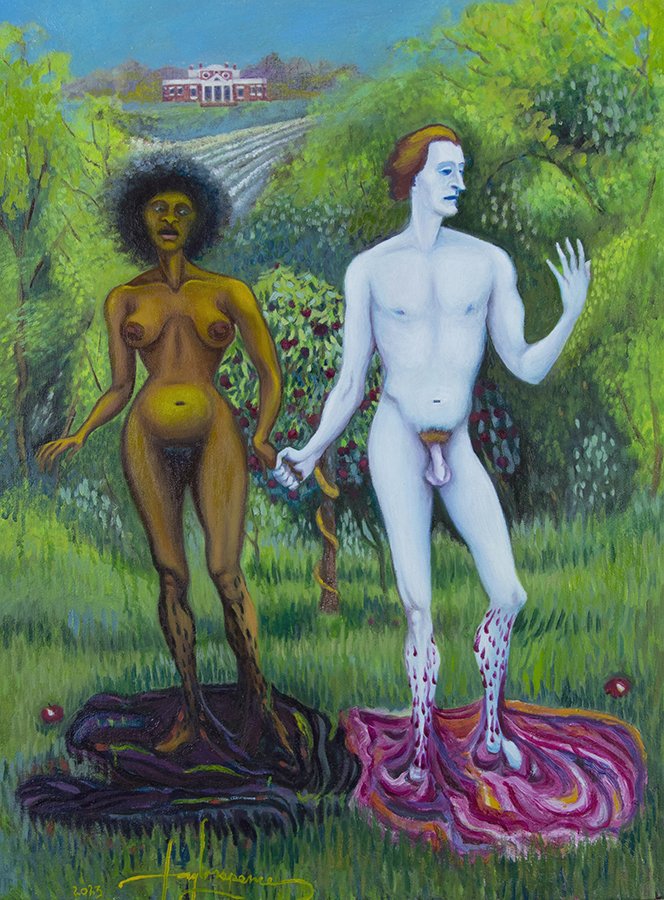

Journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones thinks there may be “many beginnings to the United States.” Yet Attucks, being by all accounts either an escaped slave or the descendant of slaves, and also probably part Native-American, uneasily carries the mantel of a founder of a nation that would enshrine chattel slavery and conduct ethnic cleansing against Indigenous Peoples. Rather, Attucks represents a longer and older tradition: that of white violence against brown people. Attucks’ murder was one murder on a long timeline of black death on this continent that began when the White Lion docked at Jamestown in 1619 and the first African slave set foot in North America. Placing Attucks’ death within this longer tradition “helps us,” according to Hannah-Jones, “understand the nation’s persistent inequalities in ways the more familiar origin story [of the United States] cannot.”[3]

An Uneasy Yet Singular Presence

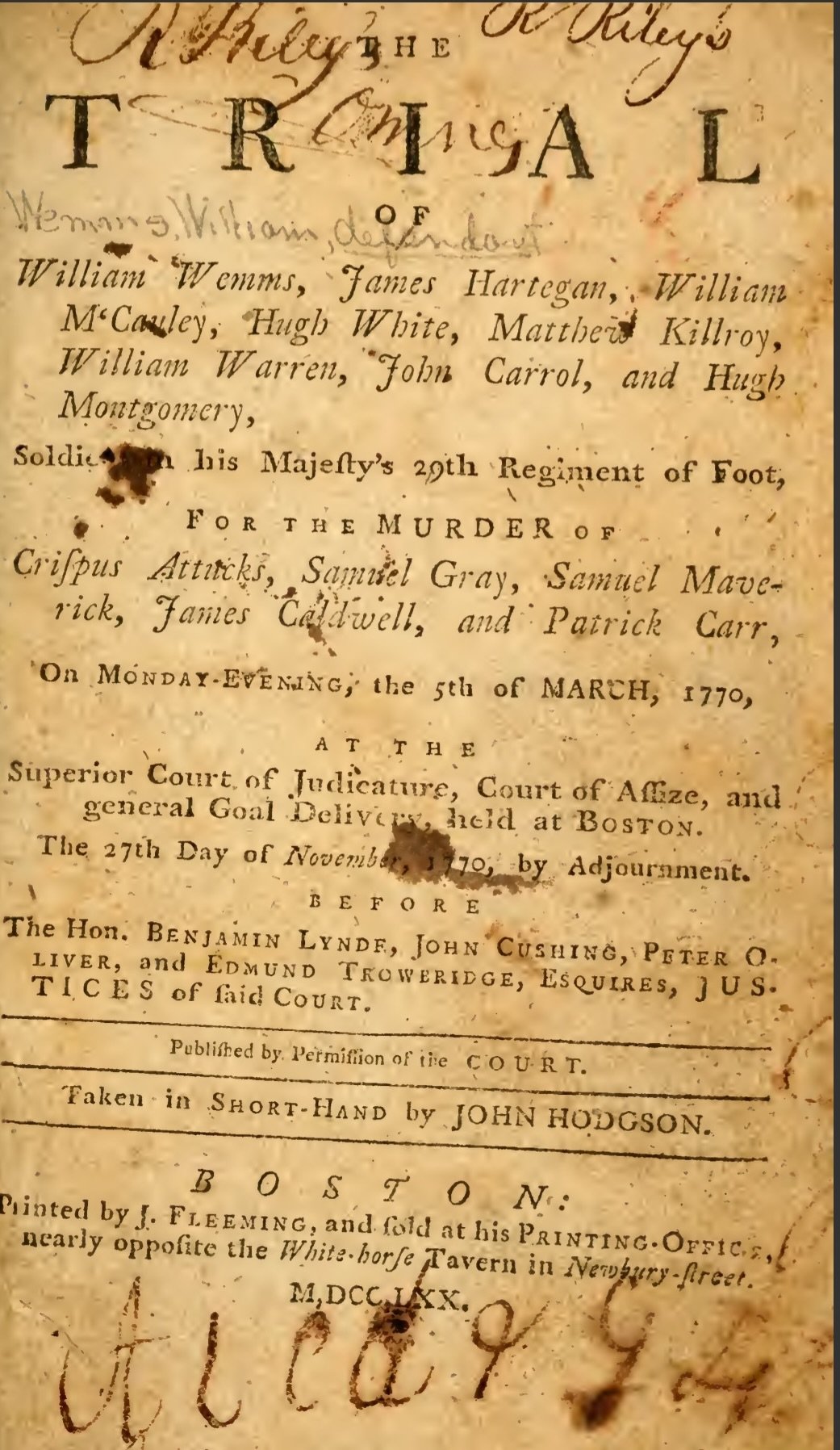

The document from which we know most about him, as well as the massacre, the transcript of the trial of the British soldiers for the murders published in 1770, is similarly unsure about Attucks (See Image). While it does not draw explicit attention to his race in its opening pages, the color of his skin was obviously significant to those who saw and remembered that night. Witnesses singled out the “molatto,” seventeen times in the transcript, even though he was not the only non-white person in the crowd.[4]

No other victim receives such intense description. With an almost hagiographic intensity the transcript describes how “leaden bullets” penetrated the black man’s “right breast, a little below the right pap of him,” and his “left breast, a little below the left pap of him” to a depth of six inches, and left one-inch-wide holes that could be easily seen.[5]

Violence against brown-skinned people was part of the fabric of the British colonies, rightfully understood as a slave society rather than a society with slaves. In 1770, British colonials overall owned 460,000 human beings as chattel, nearly all of whom were of African origin. Long before 1770 – for more than 150 years -- colonizers had been violating, punishing, isolating, and yes, murdering Africans in order to extract their labor for free.

By 1790, just twenty years after the Boston Massacre, (now) American citizens owned nearly 707,000 Africans. Subsequently and decade by decade, U.S. citizens imported and bred more African human beings so that on the eve of the Civil War in 1860, they owned nearly 4 million. Indeed, between 1619 and the end of the Civil War, 10 million human beings lived (and 60% of them died) as enslaved human property in British North America and the United States.[6]

It may have been that for the idealistic citizens of Boston, a place where slavery was relatively rare, lionizing Attucks sent a message about the radical nature of American liberty. Nevertheless, the death of one black man was neither unusual nor, in most of the colonies, a crime. Indeed, all eight soldiers were acquitted of all charges in the Boston Massacre.

The United States inherited a tradition of violence against black people, and continued this tradition. The murder of African people has been woven into the fabric of this nation from the very beginning.

Documenting the Tradition

Ida B. Wells-Barnett undertook the first systematic study of the tradition of the murder of African-Americans in 1892 after one of her friends opened a grocery store near her in Memphis, and was subsequently lynched. (See image) A courageous journalist, Wells-Barnett traveled widely in the South, investigating the claims made against Black victims of lynching, and found many of them to be unprovable, unsubstantiated, or simply false. She published her findings and then she herself was attacked, her office ransacked, and her printing press destroyed. She moved to Chicago, and continued her reporting, publishing another compendium of lynching statistics and stories in 1895. She remained an activist the rest of her life.[7]

Ida B Wells-Barnett

One of the most important aspects of Wells-Barnett’s studies was how she identified certain tropes in the stories of white murders of blacks. White truths always trumped Black ones. Black men were inherently violent and sexually deviant and thus dangerous. White lynch mobs were enacting justice in defense of their communities, not criminal violence. They worked with law enforcement, not against it, identifying and eliminating threats to the community. Significantly, Wells-Barnett wrote as if these views were already established truths, widely known, and part of long-standing tradition. The act of compiling killings in different locations and times served to reinforce the idea of a widespread tradition of racist violence.

Through the long decades of Jim Crow, the violence continued, and became normalized. Whites murdered twenty-five African-Americans in Chicago in 1919 when a black youth crossed an invisible line of segregation in Lake Michigan while swimming. Whites killed twenty-six African-Americans in Tulsa in 1921, and razed to the ground a prosperous business district, setting the community back decades. The Equal Justice Initiative, the organization behind the National Lynching Memorial in Montgomery Alabama, documented 4075 terror lynchings in 12 southern states between 1877-1950. They argue that the public nature of anti-black violence contributed to “mass incarceration, racially biased capital punishment, excessive sentencing, disproportionate sentencing of racial minorities, and police abuse of people of color.” EJI produced an animated video about this history.[8]

Several groups are documenting this tradition into the present day. The #Say Their Names organization, for example, links news reports and police records to its list of murdered black people. Other sites, Newsweek and Al Jazeera also list names. Starting with last year, 2023, #Say Their Names lists five individuals murdered by either law enforcement, other armed vigilantes, or by an unknown assailant. These people were Akira Ross, Jordan Neely, Darryl Tyree Williams, Tyre Nichols, and Keenan Anderson.[9]

In 2022, it documented the murders of Sinzae Reed, Keshawn Thomas, Dante Kittrell, Jayland Walker, Christopher Kelley, Ruth Whitfield, Pearl Young, Katherine Massey, Heyward Patterson, Celestine Chaney, Geraldine Talley, Aaron Salter, Jr., Andre Mackniel, Marcus Morrison, Roberta Drury, Patrick Lyoya, Donnell Rochester, Amir Locke, Isaiah Tyree Williams, Jason Walker, and James Williams.[10]

In 2021, law enforcement or other armed people murdered Michael Wayne Jackson, Arnell “AJ” Stewart, Fanta Bility, Alvin Motley, Jr., Ta’Neasha Chappell, Ryan Leroux, Winston Smith, Latoya Denise James, Andrew Brown, Jr., Ma’Khia Bryant, Matthew “Zadok” Williams, Daunte Wright, James Lionel Johnson, Dominique Williams, Donovon Lynch, Marvin Scott, III, Jenoah Donald, Patrick Warren, Xzavier Hill, Robert Howard, and Vincent Belmonte.[11] In 2021, law enforcement or other armed people murdered Carl Dorsey, III,[12] La Garion Smith, Tre-Kedrian Tyquan White, [13]

In 2020, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Monica Goods, Bennie Edwards, Casey Goodson, Jr., Aiden Ellison, Quawan Charles, Kevin Peterson, Jr., Walter Wallace, Jr., Jonathan Price, Kurt Reinhold, Dijon Kizzee, Damian Daniels, Anthony McClain, Julian Lewis, Maurice Abisdid-Wagner, Brayla Stone, Rayshard Brooks, Priscilla Slater, Robert Forbes, Kamal Flowers, Jamel Floyd, David Mcatee, James Scurlock, Calvin Horton, Jr., Tony McDade, Dion Johnson, George Floyd, Maurice Gordon, Cornelius Fredericks, Steven Taylor, Daniel Prude, Breonna Taylor, Barry Gedeus, Manuel Ellis, Reginald “Reggie” Payne, Ahmaud Arbery, Lionel Morris, Jaquyn O’Neill Light, William Green, Darius Tarver, and Miciah Lee.[14] In 2020, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Andre Hill.[15]

In 2020, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Modesto “Marrero Desto” Reyes, Ruben Smith, III, Jarvis Sullivan, Terrell Mitchell, Momodou Lamin Sisay, Derrick Thompson, Tyquarn Graves, Lewis Ruffin, Jr., Phillip Jackson, Michael Blu Thomas, Cane Van Pelt, Donald Ward, Brandon Gardner, Terron Jammal Boone, Derrick Canada, Skyleur Toung, Robert D’Lon Harris, Rasheed Matthew Moorman, Aloysius Larue Keaton, Kevin O. Ruffin, Ky Johnson, William Wade Burgess, Joseph W. Denton, Paul Williams, Malik Canty, Erroll Johnson, Richard Lewis Price, Hakim Littleton, Vincent Demario Truitt, Aaron Anthony Hudson, Darius Washington, Vincent Harris, Jeremy Southern, Name Withheld By Police, Chester Jenkins, David Earl Brooks, Darrien Walker, Ashton Broussard, Amir Johnson, Salaythis Melvin, Jonathan Jefferson, Rafael Jevon Minniefield, Kendrell Antron Watkins, Adrian Jason Roberts, Treyford Pellerin, Julius Paye Kehyei, Michael Anthony Harris, Robert Earl Jackson, Deon Kay, Steven D. Smith, Major Carvel Baldwin, Steve Gilbert, Jonathan Darsaw, Robert Coleman, Darrell Wayne Zemault Sr., Charles Eric Moses Jr., Dearian Bell, Patches Vojon Holmes Jr., Willie Shropshire Jr., DeMarco Riley, Stanley Cochran, Tyran Dent, Anthony Jones, Kevin Carr, Dana Mitchell Young Jr., Fred Williams III, Akbar Muhammad Eaddy, Dominique Mulkey, Marcellis Stinnette, Rodney Arnez Barnes, Gregory Jackson, Mark Matthew Bender, Ennice "Lil Rocc" Ross Jr., Jakerion Shmond Jackson, Maurice Parker, Justin Reed, Michael Wright, Reginald Alexander, Jr., Frederick Cox, Jr., Rodney Eubanks, Vusumuzi Kunene, Brandon Milburn, Tracey Leon McKinney, Angelo "AJ" Crooms, Sincere Peirce, Arthur Keith, Shane K. Jones, Shawn Lequin Braddy, Jason Brice, Kenneth Jones, Rodney Applewhite, Terrell Smith, Rondell Goppy, Ellis Frye, Jr., Cory Donell Truxillo, Mickee McArthur, Udofia Ekom-Abasi, James David Hawley, Kevin Fox, Dominique Harris, Maurice Jackson, Andre K. Sterling, Kwamaine O'Neal, Mark Brewer, Donald Edwin Saunders, Thomas Reeder, III, Joseph R. Crawford, Joshua Feast, Charles E. Jones, Jeremy Daniels, Johnny Bolton, Larry Taylor, Isaac Frazier, Sheikh Mustafa Davis, Shamar Ogman, Marquavious Rashod Parks, Larry Hamm, Helen Jones, Jason Cooper, Jaquan Haynes, Shyheed Robert Boyd, and Dolal Idd.[16]

In 2019, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered John Neville, Cameron Lamb, Michael Dean, Atatiana Jefferson, Byron Williams, Elijah McClain, Jaleel Medlock, Titi “Tete” Gulley, Dominique Clayton, Pamela Turner, Ronald Greene, Sterling Higgins, Bradley Blackshire, and Jassmine McBride.[17]

In 2018, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Aleah Jenkins, Emantic Bradford, Jr., Jemel Roberson, Charles Roundtree, Jr., Botham Jean, Harrith Augustus, Jason Washington, Antwon Rose, Jr., Robert White, Earl McNeil, Marcus-David Peters, Dorian Harris, Danny Ray Thomas, Stephon Clark, and Ronell Foster.[18]

In 2017, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Damon Grimes, James Lacy, Charleena Lyles, Mikel McIntyre, Jordan Edwards, Timothy Caughman, Alteria Woods, and Desmond Phillips.[19]

In 2016, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Deborah Danner, Alfred Olanco, Terence Crutcher, Christian Taylor, Jamarion Robinson, Donnell Thompson, Jr., Joseph Mann, Philando Castile, Alton Sterling, Jay Anderson, Jr., Che Taylor, David Joseph, and Antronie Scott.[20]

In 2015, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Bettie Jones, Quintonio Legrier, Corey Jones, Samuel Dubose, Darrius Stewart, Sandra Bland, Susie Jackson, Daniel Simmons, Ethel Lance, Myra Thompson, Cynthia Hurd, Depayne Middleton-Doctor, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Clementa Pinckney, Tywanza Sanders, Kalief Browder, Freddie Gray, Norman Cooper, Walter Scott, Eric Harris, Meagan Hockaday, and Natasha McKenna.[21] In 2015, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Janisha Fonzille.[22]

In 2014, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Rumain Brisbon, Tamir Rice, Akai Gurley, Tanisha Anderson, Laquan McDonald, Cameron Tillman, Darrien Hunt, Kajieme Powell, Michelle Cusseaux, Dante Parker, Ezell Ford, Michael Brown, Amir Brooks, John Crawford, III, Eric Garner, Jerry Dwight Brown, Victor White, III, Marquise Jones, and Yvette Smith.[23] In 2014, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Aura Rosser and Gabriella Navarez.[24]

In 2013, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Renisha McBride, Jonathana Ferrell, Deion Fludd, Gabriel Winzer, Wayne A. Jones, Kimani Gray, and Kayla Moore.[25]

In 2012, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Corey Stingley, Darnesha Harris, Jordan Davis, Mohamed Bah, Sgt. James Brown, Darius Simmons, Rekia Boyd, and Trayvon Martin.[26]

In 2011, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Willie Ray Banks, Kenneth Chamberlain, Sr., Cletis Williams, and Robert Ricks.[27]

In 2010, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Eugene Ellison, Danroy “DJ” Henry, Jr., and Aiyana Stanley-Jones.[28]

In 2009, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Lawrence Allen, and Oscar Grant.[29]

In 2008, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Julian Alexander and Marvin Parker.[30]

In 2007, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Deaunta Farrow, aged 12.[31]

In 2006, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Sean Bell and Kathryn Johnston.[32]

In 2005, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered

In 2004, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Timothy Stansbury, Jr.[33]

In 2003, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Alberta Spruill.[34]

In 2002, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered

In 2001, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered

In 2000, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Anthony Dwain Lee.[35]

In 1999, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Ricky Byrdsong and Amadou Diallo.[36]

In 1998, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered James Byrd, Jr.[37]

In 1994, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Nicholas Heyward, Jr.[38]

In 1990, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Mary Mitchell.[39]

In 1984, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Sharon Walker and Eleanor Bumpurs.[40]

In 1974, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Edward Garner.[41]

In 1971, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Elton Hayes.[42]

In 1969, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Fred Hampton.[43]

In 1968, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Martin Luther King, Jr.[44]

In 1965, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Alberta Odell Jones, Jimmie Lee Jackson, and Malcolm X.[45]

In 1964, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered James Earl Chaney and Louis Allen.[46]

In 1963, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Medgar Evers.[47]

In 1961, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Herbert Lee.[48]

In 1955, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered John Earl Reese and Emmett Till.[49]

In 1954, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered William McDuffie.[50]

In 1953, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Della McDuffie.[51]

In 1949, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Malcolm Wright.[52]

In 1944, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered George Stinney Jr.[53]

In 1921, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Dr. Andrew C. Jackson.[54]

In 1919, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Will Brown.[55]

In 1882, law enforcement or other armed citizens murdered Levi Harrington.[56]

This list cannot, of course, be complete.

The murder of black people by whites is a tradition older than the United States.

[1] Mitch Kachun, First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 47, 74–75; Hannah-Jones, The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, 11.

[2] Architect of the Capitol, “Declaration of Independence,” accessed September 5, 2023, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/declaration-independence.

[3] Nikole Hannah-Jones, The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story (New York: Random House, 2021), xxxii.

[4] Council for the defense John Adams, exhorted the jury to sympathize with the soldiers, surrounded as they were by a mob of angry people including, “negroes and molattos.” John Hodgson, The Trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William M’Cauley, Hugh White, Matthew Killroy, William Warren, John Carrol, and Hugh Montgomery, for the Murder of Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, and Patrick Carr (Boston: J. Fleeming, 1770), 4, 13, 26, 27, 28, 31, 41, 47, 61, 101, 103, 114, 153, 163, 176.

[5] Compare this description to Christopher Regnaut’s account in the Jesuit Relations of seeing and touching “the top of [Father Brebœuf’s] scalped head; [and] the opening which these barbarians had made to tear out his heart.” Seeing and touching the martyr’s wounds was proof both of humanity but also divinity. Ruben Gold Thwaites, ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, trans. Crawford Lindsay et al. (Creighton University), Vol. 34, 25-37, accessed October 6, 2016, http://moses.creighton.edu/kripke/jesuitrelations/; Hodgson, The Trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William M’Cauley, Hugh White, Matthew Killroy, William Warren, John Carrol, and Hugh Montgomery, for the Murder of Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, and Patrick Carr, 4.

[6] J. David Hacker, “From ‘20. and Odd’ to 10 Million: The Growth of the Slave Population in the United States,” Slavery & Abolition 41, no. 4 (2020): 840–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039x.2020.1755502.

[7] Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (Afro-American Women of New York and Brooklyn, at Lyric Hall, 1892), https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/634281e0-4abc-0134-346c-00505686a51c; Ida B. Wells-Barnett, The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States (Project Gutenberg, 1895), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/14977/14977-h/14977-h.htm; “Biography: Ida B. Wells-Barnett,” National Women’s History Museum, accessed December 22, 2024, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ida-b-wells-barnett.

[8] Equal Justice Initiative, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.”

[9] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames,” accessed January 25, 2024, https://sayevery.name/.

[10] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[11] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[12] Sophie Nieto-Munoz, New Jersey Monitor January 31, and 2023, “Family of Man Killed by Newark Police Officer Wants Federal Probe,” New Jersey Monitor (blog), January 31, 2023, https://newjerseymonitor.com/2023/01/31/family-of-man-killed-by-newark-police-officer-wants-federal-probe/.

[13] “Full List of 229 Black People Killed by Police Since George Floyd’s Death,” Newsweek, May 25, 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-229-black-people-killed-police-since-george-floyds-murder-1594477.

[14] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[15] Al Jazeera, “Know Their Names: Black People Killed by the Police in the US,” accessed January 25, 2024, https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2020/know-their-names/index.html.

[16] “Full List of 229 Black People Killed by Police Since George Floyd’s Death.”

[17] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[18] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[19] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[20] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[21] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[22] Jazeera, “Know Their Names.”

[23] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[24] Jazeera, “Know Their Names.”

[25] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[26] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[27] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[28] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[29] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[30] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[31] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[32] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[33] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[34] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[35] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[36] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[37] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[38] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[39] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[40] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[41] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[42] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[43] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[44] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[45] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[46] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[47] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[48] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[49] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[50] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[51] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[52] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[53] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[54] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[55] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”

[56] “📢 Say Their Names List 2023 — #SayTheirNames.”